Heimat

Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17

series of 53 photographs,

40 × 26,7 cm; 40 × 60 cm; 60 × 40 cm; 100 × 66,7 cm; 66,7 x 100 cm,

chromogenic prints

|

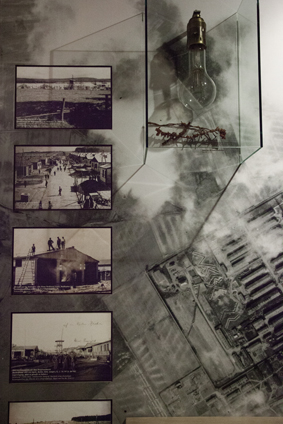

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 1), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 100 × 66,7 cm. Gedenkstätte und Museum Trutzhain, 13.11.2016. Housed in a former barracks, the Trutzhain Museum documents the history of the prisoner of war camp STALAG IX A Ziegenhain and the expellees who were resettled there in 1948. The partially depicted display board presents an aerial view of the site and photos of the construction of the barracks, as well as a light bulb and a piece of barbed wire from the camp. Following the invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, Poles, Frenchmen, Belgians, Yugoslavs, and Americans were kept at the camp; from 1941 Soviet and Serbian prisoners were interned here too, living under atrocious conditions with almost all of them dying. At the end of the war, the camp was used to imprison German members of Nazi organisations and later to house first displaced persons and then expellees. In 1951 it was turned into the municipality of Trutzhain. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 2), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Historische Weberei Egelkraut, Trutzhain, 11.03.2017. In 1947 Rudolf and Robert Egelkraut established a weaving factory in a barrack at the former STALAG IX A Ziegenhain prisoner of war camp. They were expellees from the Egerland, located in the west of present-day Czech Republic. At first the Egelkraut family produced household fabrics including fabric needed for traditional costumes made by the local population. In the beginning of the 1950s, however, they started to produce elaborate tapestries that were exported worldwide. In 1953 they commissioned the factory building where the company continues to be run today–still using the historical looms–by a former employee of the Egelkraut family, Udo van der Kolk. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 3), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Trutzhain, 26.04.2017. In 1964 the owner of the depicted barracks built an extension on the front side of the building to make it more comfortable. Although the former camp as a whole has been declared a protected monument, the inhabitants renovated their homes across the years. Some barracks, however, are quite dilapidated, especially premises that house factories or storage facilities. In contrast to its appearance today, Trutzhain was a flourishing commercial production site in the 1950s–thanks to the expellees' skills and motivation–where people from the surrounding area came to work. Noteworthy facilities were the artificial flower factory, the weaving factory, and the sauerkraut, crate, and barrel factory. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 4), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Gemeindefriedhof, Trutzhain, 11.03.2017. Two separate cemeteries were part of the STALAG IX A Ziegenhain. Today's local cemetery is the former burial place for Western Allied and Polish prisoners. Soviet and Serbian prisoners of war, however, were buried anonymously at a remote cemetery located in the nearby forest; Italian military internees were also buried there. As of approximately fifteen years ago, the tombstones of expellees have been relocated to a special memorial site when their grave sites at the local cemetery are closed. The explanation on the horizontal plate reads, "Tomb stones of deceased refugees and expellees. Since spring 1948 the former P.O.W. camp STALAG IX A Ziegenhain becomes a New Home for expellees and refugees from the German eastern territories and the Sudetenland. The inscriptions on the tombs evoke the origins and former homes of the deceased." Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 5), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Gedenkstätte und Museum Trutzhain, 16.03.2017. Blumen made in Trutzhain (Flowers made in Trutzhain), a film by Julia Charlotte Richter, was released in 2013. It tells the story of E. W. Lumpe's artificial flower factory, established in 1948, by tracing the dire living conditions of expellees in Trutzhain, the optimism and success of the founders of the factory, and their eventual failure when they were unable to compete with global production. As such, the film is part of the memorial site that Trutzhain has come to be. It also recalls a time when flowers made from crepe and silk were a feature of fashion and used in burial rituals. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 6), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Christian Steidl and Renate Holtsche, Kunstblumenfabrik Lumpe, Trutzhain, 16.03.2017. Renate Holtsche was born near Trutzhain and came to live in the former camp in 1949 with her family, who were expellees from the Sudetenland. All the inhabitants of Trutzhain were expellees, but people from the surrounding areas came to the settlement to work and also for the festival. The photo shows Ms. Holtsche returning to E. W. Lumpe & Son's defunct artificial flower factory, where she occasionally worked. The factory was established in 1948–one of the first factories in the camp—in a building that had been used as a synagogue by displaced persons in 1946. The Lumpe family had originally been expelled to Thuringia in the Soviet occupation zone, where they established a first artificial flower factory. They decided, however, to take flight again when their property in Thuringia was expropriated. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 7), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Wallfahrtskirche Maria Hilf, Trutzhain, 11.03.2017. In 1964/65 the Church of Our Lady of Perpetual Succour in Trutzhain was constructed in the shape of a tent. Expellees from the Sudetenland transferred an ancient pilgrimage to their new home, the former prisoner of war camp STALAG IX A Ziegenhain. The original pilgrimage relates to a legendary event in 1342, near Quinau in the Bohemian Erzgebirge (Ore Mountains). For the Trutzhain pilgrimage, a statue of the Virgin Mary was carved and clad in fabric produced by the Trutzhain weaving factory Rudolf Egelkraut. The statue was carried in a procession from Neukirchen to Trutzhain. This, however, aggravated conflicts between expellees and native inhabitants caused by their different faiths. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no.8), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 66,7 x 100 cm. Friedhof Treysa, Schwalmstadt, 13.11.2016. Expellees from the Sudetenland and western Prussia, participating with locals in the dedication of a bronze plate to the memory of German civilian victims of the Second World War, at the Kreuz des Ostens (Cross of the East) at Treysa cemetery in Schwalmstadt. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 9), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Friedhof Treysa, Schwalmstadt, 13.11.2016. Celebration at the war memorial at the Treysa cemetery in Schwalmstadt, on Volkstrauertag (Remembrance Sunday). The memorial is inscribed with the names of men and recall the years of the First and Second World Wars. The main inscription reads, "To the dead of both World Wars." Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 10), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Friedhof Treysa, Schwalmstadt, 13.11.2016 On November 13, 2016 a second bronze plate was unveiled at the Kreuz des Ostens (Cross of the East) at Treysa cemetery in Schwalmstadt. The cross is one of several hundred on mountains and at cemeteries across Germany. It was erected in 1950/51, and the dedication on the first bronze plate from 1987 reads, "To the memory of flight and expulsion 1945. To the remembrance of the dead, to the admonition of the living." The second plate is inscribed, "To the memory of the millions of victims of flight, expulsion, deportation, bombing, and imprisonment during and after the Second World War." The second plate was initiated by Horst Gömpel, Marianne Wawrauschek, and Adolf Lauscher in conjunction with the city of Schwalmstadt. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 11), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 60 x 40 cm. Friedland-Gedächtnisstätte, Friedland, 13.11.2016. Consisting of four concrete slabs, each twenty-eight metres high, the memorial at the Friedland border transit camp features twelve plates with inscriptions that refer to the consequences of the Second World War and almost exclusively to the German victims. The plates dedicated to the expelled and the deported read as follows: "Fifteen million Germans were expelled in 1945 from their homes east of the Oder-Neisse line and the Bohemian Forest, from east and southeast Europe."—"One million German civilians were deported to the wide stretches of the East from 1944–47, among them women and children."—More than two million innocent people were victims of the expulsion, dying miserably on the roads from exhaustion or by human violence."—"People, come together!" During the New Year of 1967/68, unknown activists wrote on two of the plates, "Dachau" and "Lidice." Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 12), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 26,7 cm. Friedhof Guxhagen, 11.03.2017. The arrival of expellees in small villages and towns not only resulted in a sharp increase in population, but also in members of the church. The majority of expellees from the Sudetenland adhered to Catholicism. As a consequence, the Catholic congregation at the town of Melsungen, for instance, grew from 300 to 6,000 members in the years after the Second World War. St. Michael's Church, located at Sudetenstrasse in Guxhagen, belongs to this community; it was built in 1960 at the initiative of Catholic expellees. The horizontal bar of the memorial cross, erected in 1952 at the entrance of the Guxhagen cemetery, features the inscription, "To the dead at home." Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 13), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 26,7 cm. Friedhof Neukirchen, 25.03.2017. After the Second World War, almost 10,000 people from the Sudetenland were relocated to Ziegenhain (now Schwalm–Eder) district in Northern Hesse. The inscription on the stone plate behind the memorial cross reads, "To the memory of the dead, as an obligation for the living. 1950. The expellees of Ziegenhain." Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 14), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 26,7 cm. Friedhof Besse, Edermünde, 25.03.2017. Until after 1949, expellees were prevented from convening in associations or parties with political goals. The American military administration, particularly, feared the radicalization of expellees who were, compared to the native population, disadvantaged in social and economical terms. Also the dispersion of expellees was intended to disrupt social bonds. When pressure diminished, expellees started to create interregional associations which had three to four million members at the beginning of the 1950s. The "Charter of the German Expellees" declared in August 1950, "We, the expellees, renounce all thought of revenge and retaliation." The inscription behind the memorial cross at the cemetery of Besse (Edermünde) reads, "In memory of the dead from home. The expellees of the community of Besse. Easter 1981." Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 15), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Reinhard Besse, Kassel, 27.04.2017. Reinhard Besse's mother arrived in Hesse in 1945 or 1946 from an area around Frankfurt (Oder) that became part of Poland after the Second World War. She probably walked all the way, bringing only her papers. Mr. Besse believes that his mother was raped by Soviet soldiers during her flight. She was regarded with suspicion by the people of her new village. She had come with nothing and married a farmer's son. She also didn't speak dialect and supported other refugees. At the beginning of the 1970s, Mr. Besse's mother visited her former home in Poland, where she was even invited into the house by the people now living there. Those people in turn had been expelled from the eastern part of of the country when it became part of the Soviet Union. Mr. Besse's mother never planned to get her property back. She said that kind of thinking would lead to another war. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 16), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Ellie Rosa and Otto Renner, Fritzlar, 09.11.2016. In his living room Otto Renner demonstrates how Sudeten Germans were tortured by Czech armed units after the fall of Nazi Germany. In his home town in the Sudetenland, in two hotels, people were forced to stand close to the wall and were then hit on the back of the head. Mr. Renner talked also about the executions of native Germans that he was told about by a colleague. The photo next to him shows his "ancestors"; it is his parents' wedding photo. The other photo shows his great grandfather with his family when they were Austrian-Hungarian subjects. He said that his "home" is the Riesengebirge (Giant Mountains), while he is "at home" in Fritzlar, a town near Kassel. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

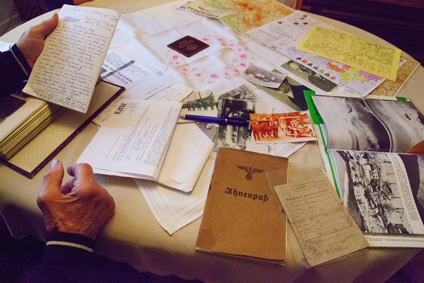

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 17), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Ellie Rosa and Otto Renner, Fritzlar, 09.11.2016. Documents relating to Otto Renner's past in the Sudetenland. The Ahnenpass (ancestor passport) was issued by the Nazi authorities after the incorporation of the Sudetenland into the German Reich in 1938. It served to prove Aryan ancestry. The document in Czech served as an identity document after the Sudeten—Germans lost their German citizenship in 1945. The handwritten text is Mr. Renner's copy of an announcement by Soběslav I, Duke of Bohemia (ca. 1075–1140), granting Germans settling in Bohemia protection and the right to maintain their own national identity. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

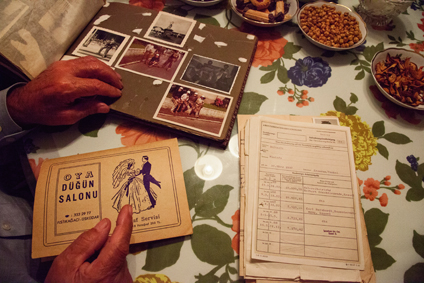

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 18), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Türkan and Mustafa Defterli, Kassel, 03.11.2016. Dire need forced Mustafa Defterli to leave his hometown, Erzurum in eastern Anatolia, at the age of thirteen. He went to Istanbul to start an apprenticeship as a painter. In 1961 he was married in Erzurum to his wife Türkan, and she moved with him to Istanbul. Out of curiosity and love of adventure he applied for guest work in Europe. In 1965 he travelled by train to Munich and later arrived in Kassel where he began to work for a painter. Mr. Defterli ate pork for the first time and was at first hardly able to communicate. The Defterlis had two small daughters and in 1968 Ms. Defterli and the two children came to Kassel where two additional children—a boy and a girl—were born. Mr. Defterli presents photos that were taken soon after his arrival in Germany, an envelope with wedding photos, and a pension insurance certificate. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 19), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Ellie Rosa and Otto Renner, Fritzlar, 09.11.2016. Otto Renner was born and raised at Spindlermühle in the Sudetenland. When he was fifteen years old, Renner and his grandparents were expelled from their home. On March 6, 1946 they were taken to Hohenelbe and loaded into a cattle car (thirty persons per car; forty cars per train) to arrive in Gemünden, in the Waldeck-Frankenberg district in Hesse, on March 10. His parents and his siblings, who had Socialist inclinations, were sent to the Soviet Occupation Zone by "privileged anti-fascist transport." After arriving in Hesse, his grandfather got a job clearing an ammunition depot. Mr. Renner claims that the ammunition was sent to France and believes it may have been used in the French colonial wars. In the photo Mr. Renner displays the Sudetenland flag. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 20), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Gerda Stock, Trutzhain, 25.03.2017. The photo depicts Gerda Stock in the basement of her house in Trutzhain, where she works a rotary iron in spite of her age. In 1945 her family's landlord in Silesia had taken her mother and three children with him on his flight; on the way, her six-week-old brother starved to death. Her grandmother stayed in Silesia with her two other daughters; her grandfather was executed, because he didn't speak Polish. The flight of Ms. Stock and her children first came to an end in Halle in the Soviet Occupation Zone, where they stayed until 1949. Ms. Stock remembers her shock when arriving at Trutzhain: "Not a camp again!" But the solidarity among the expellees, the opportunity to earn money, and the feeling of freedom caused Ms. Stock to remain in Trutzhain. "We have created here a new home." Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 21), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Carmen Rivas Bouzón, Sebastian Pérez Furest and Michéle Pérez Rivas, 16.11.2016. Erundina Bouzón Couñago moved from Vigo to Lippstadt in 1960; her husband followed a year later. In Vigo, Ms. Couñago had worked for a fee of two pesetas at a hotel and raised pigs. Her daughter, Carmen, was born in Kassel and didn't speak Spanish. She had to return to Spain with her family, however, when her father fell ill. There she was sent to a monastery boarding school. At the age of fourteen, Carmen returned to Kassel, but she no longer spoke German. Meanwhile, her father had died and her mother worked as a cleaning lady at a hospital in Kassel. For a while, the mother and daughter lived together in Kassel, in one room. Carmen Rivas Bouzón says that she has two homes, as one has two parents. The picture shows a letter by her sister, Rosa, talking about her plans to marry. Next to the letter, a wedding photo of a relative can be seen. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 22), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Ingrid and Dietmar Pfütz, Kassel, 04.11.2016. Dietmar Pfütz was born in Niklasdorf in the Sudentenland. In 1946, at the age of four, he was forced to leave his home and expelled to the West with his mother and several relatives. The farmer who was obliged to receive them was unfriendly and they were called gypsies by the locals. In 1947 his father, a German prisoner of war in the Soviet Union, returned home and in 1956 his parents built a house of their own. Eventually Mr. Pfütz became the district chairman of the Sudetendeutsche Landsmannschaft, an influential association of expellees. "We can forgive, but not forget." Mr. Pfütz said that he has two homes: the Altvater mountains of his origin and Northern Hesse. He has been back to his native village several times and is involved in dialogues that aim for reconciliation with the Czech authorities and the current inhabitants of his birthplace. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 23), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Marlene and Horst Gömpel, Schwalmstadt, 08.11.2016. For several years Horst and Marlene Gömpel have been committed to keeping alive the memory of the suffering of German civilians during and after the Second World War—especially expellees and refugees—and also acknowledging the efforts of the local populations affected by the resettlements. They have published, for instance, documentation of the expulsions from the Sudetenland region and the subsequent resettlement of populations in Northern Hesse. They have also initiated the placement of memorial plates in various locations. As a child Ms. Gömpel and her family were expelled from Reischdorf, a village near Komotau in the Sudetenland that no longer exists; Mr. Gömpel is originally from Hesse. Ms. Gömpel says that she has two homes, an old and a new one. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 24), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 66,7 x 100 cm. ÄnderungsSchneiderei, Kassel, 09.03.2017. Bülent Kocabay owns a tailoring shop in Kassel that was founded by his father in 1982. His father arrived at the beginning of the 1970s as a guest worker. Before moving to Germany, his mother and his father had migrated from Anatolia to Istanbul. Nowadays his parents spend most of the time in Turkey, but they return regularly to Kassel. Mr. Kocabay says that he is at home both in Turkey and in Germany, however also speaks of Islamophobia, xenophobia, and hatred of Turks. "Discrimination destroys you." He needs to live in Germany, where he has his work and his social network. He would move back to Turkey if everything went wrong, but he would have to start again from zero. Mr. Kocabay is member of the Kassel City Mosque and also member of the new migrants' party, the Allianz Deutscher Demokraten (ADD). Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 25), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 66,7 x 100 cm. FERTOURS Travel Agency, Kassel, 13.03.2017. Riza Osmanaj in the office of FERTOURS Travel Agency, the bus tour operator he runs together with his son Korab. Mr. Osmanaj's father, Mehmet, came to Kassel from Kosovo in 1972 to work at Mercedes; he assumed that he would return home after a few years, so he left his wife and three children in Kosovo. Riza studied agriculture in Kosovo and before coming to Kassel in 1994 to join his father he took German classes. One of his brothers stayed in Kosovo, while the other emigrated to Texas. Mehmet Osmanaj's wife came to Kassel only after he retired, in the mid-1990s. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 26), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 66,7 x 100 cm. Türkischer Rentnerverein Emekder, Kassel, 17.03.2017. Vahiddin Oğuz, the president of the Turkish Retiree Association Emekder, meets a visitor at his office. The photograph behind him depicts the first president of the Republic of Turkey, Kemal Atatürk. The association offers a meeting place for Turkish senior citizens, as well as counseling in all administrative matters, especially issues connected to retirement. Clients are Turkish, Romanian, or Bulgarian, most of them from Bettenhausen. Mr. Oğuz who had been trained as a teacher of sports and mathematics in Turkey, accepted the offer to become a teacher of Turkish at a primary school in Kassel in 1969. He remembers that when he was first looking for a flat in Kassel, a Turkish person told him, "Go to gypsy street," referring to Oestmannstrasse. Of the Nordstadt neighborhood in Kassel he says, "It's getting better all the time." Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 27), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 66,7 x 100 cm. Rathaus Kassel, 03.03.2017. Murat Çakır's presence as a translator is required at the wedding of Çiğdem Yalcin and Göksel Akgül at Kassel City Hall because the groom, originating from Izmir in Turkey, doesn't speak German. The young people met during the bride's vacation in Turkey and decided to establish themselves at the center of her life. Mr. Akgül will work in Kassel at the bride's father's advertising agency. Mr. Çakır considers this photograph of the wedding ceremony important because the presence of the translator demonstrates that Germany is, and has been for long a time despite all political denial, a country of immigrants. The bride's father is called Hüseyin Yalcin and belongs to the second generation of guest workers. The witnesses are Jessica Seitz and Senem Korkmaz. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 28), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 66,7 x 100 cm. El Torito—Spanische Spezialitäten, Kassel, 08.03.2017. Maria Dolores Sabates Juliana came to Kassel in 1973 from Barcelona. Adolfo Suarez came before Ms. Juliana from Madrid. Mr. Suarez worked at Volkswagen as a guest worker. Ms. Juliana was a Spanish teacher and offered private tutoring to students. In 1999 she opened her shop on Holländische Strasse. Mr. Suarez retired in 2009. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 29), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Clubhaus, FC Bosporus Kassel, 27.02.2017. Bek Engin, Hasan Karaçam, Süleyman Gül, Kazim Gül, and Ismet Samed celebrating at the clubhouse of FC Bosporus Kassel. They are united by a passion for soccer. The first generation of Turkish guest workers arriving in the region found it difficult to integrate, due to a lack of knowledge of the German culture and language on the one hand, and exclusion, discrimination, and racism on the other. There was a desire to make it easier for the next generation, and the club was established in 1980. It was an internationalist, comprehensive social project. As the founding president of the club, Murat Çakır, explained, "Sport was a means to an end." From the beginning, discussions about politics and religion were discouraged in order keep the club open to a broad spectrum of youths. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 30), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Café Zanetti, City Point, Kassel, 13.03.2017. At the end of the 1970s, the Greek community had a meeting place at the Schlachthof Cultural Centre, but it was dissolved when the economic crisis of the 1980s meant that many Greeks working in the industrial sector returned home. Today, a number of Greek retirees meet habitually before lunch at Café Zanetti in the City-Point shopping center. Mr. Filippos—in the center-right of the picture—came to Germany in 1960. Next to him sits Rigas Dimitrios, manager of a Greek–German restaurant in Kassel since the beginning of the 1980s. They are framed by Maria and Nikos Abadzianis, who belong to a younger generation. Mr. Abadzianis arrived in 1972 and met his wife Maria in Kassel in 1995, where they both still live. Being connected to both Germany and Greece means to be at home in two places. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 31), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Club Juvenil, Kassel, 04.03.2017. The 1973 oil crisis marked a changing point in the lives of the first generation of guest workers. Many decided to speed up reunion with their children and partners, and new social, political, and cultural needs were created as new members of the family arrived. As a consequence, the Club Juvenil (Youth Club) was established in 1974. Later the club became a founding member of the Schlachthof Culture Center, where it has been based since 1978. The club is open for members of the Spanish community and sympathizers. In addition to being a regular meeting point, the Club Juvenil also organizes cultural events. At first, it was needed to counter the discrimination against young people; now it contributes to the integration of their children. Depicted are Antonio Alejos, Sebastian Pérez Furest, Juan Lozano Marchena, and Francisco Pérez Furest. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 32), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Cem Evi, Kassel, 28.02.2017. The Cem Evi near Kassel city centre is the house of the Alevi religious denomination. For the Alevis, emigration to Europe effected their liberation from religious and political discrimination by the Sunni majority in Turkey. The Cem Evi includes a space for prayer and a library; the space for retirees is reserved for men, while other spaces are shared by men and women. The Cem Evi offers seminars and courses. During Muharrem people fast together, and the celebration of circumcision, the traditional Turkish wedding-eve party, or the burial ritual may take place at the Cem Evi. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 33), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Nesrin Studio für Kopfhaut- und Haarpflege, Kassel, 01.03.2017. Murat Çakır is seen with his mother, Necla Çakır outside his wife's barber shop. In 1970 he followed his father, who had arrived in 1967 as a guest worker. "At ten I did everything on my own." His mother came in 1971, his brothers one year later. He however returned to Turkey, where he graduated from high school. In 1979 he joined the Turkish Communist Party; later he studied in Germany, became a translator and building promoter. In 2004 Mr. Çakır was a founding member of the WASG (Labor and Social Justice—The Electoral Alternative), in 2017 he ran in Kassel for Lord Mayor on the ticket of Die Linke (The Left). He said, "My home is my wife, my friends, my social network. My fatherland is the earth, my nation is humanity." He describes himself as an internationalist and cosmopolitan and at the same time as a Kassel patriot. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 34), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 66,7 x 100 cm. FC Bosporus Kassel, 05.03.2017. The soccer club FC Bosporus Kassel was founded in 1980 by Turkish guest workers. The name "Bosporus" is easy to pronounce, symbolizes the relation of the club to its roots, and refers to a bridge between Turkey and Europe. The Federal Ministry of the Interior supports the club within the framework of the Integration durch Sport (Integration through Sport) program. In 2016 the club was promoted to the Verbandsliga (fifth division) and is now struggling to consolidate this success and to increase the number of members. The players in the picture are: Ismet Yegül (Turkey), Nima Latifiahvas (Iran), Ugur Kahraman (Turkey), Abdullah Alidrisi (Libya), Omar Bayoud (Libya), Mirko Tanjic (Croatia), Nihat Cemali (Turkey), and Kai Steinert (Germany). Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 35), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Kroatische katholische Mission, Elisabethkirche, Kassel, 14.04.2017. The photo shows Andelko Dopar, Davor Juričić, and Luka Pavić at the Church of St. Elizabeth in Kassel during a service by the Croatian Mission. Mr. Juričić was born in Hagen, Germany, but was raised in Croatia until his family decided to move back to Germany in 1988, when he was sixteen years old. Luka Pavić, born in Germany, is a third generation descendant of a guest worker. The Catholic service offers a way to preserve traditions of song and prayer and to speak the same language. "Majka Božja Marija, the Mother of God, is considered the Queen of the Croatian Nation," says Mr. Dopar. He arrived in Kassel at the age of twenty-five to join his wife, who is from Kassel with roots in the former Yugoslavia. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 36), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Türkischer Rentnerverein Emekder, Kassel, 17.03.2017. Ekrem Öztatlı, Metin Baykan, Necmeddin Tunalı, Feridun Kahraman, and Yahya Bağrıaçık prepare themselves for prayer in an adjoining room that is also used as a library, at the Emekder retiree association. It is preferable not to pray alone, but together with other believers. Mr. Kahraman (standing in the doorway) came as a guest worker to Germany and worked as a shoe maker and in construction. He studied the Quran and before leaving home served at the mosque as a muezzin. If asked, he could assume the function of the imam at prayer. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 37), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Griechisch-orthodoxer Gottesdienst, Alte Brüderkirche, Kassel, 19.03.2017. As a consequence of the recruitment agreement between West Germany and Greece, people from different areas of Greece have been moving to Kassel since 1960. In 1963 the Greek Orthodox Metropolis of Germany was established, a Greek Orthodox diocese subordinated to the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. As a consequence, it has been possible to celebrate a Greek Orthodox liturgy every third Sunday of the month since 1965, at the Old Church of the Brethren. Parallel venues of social, cultural, and political encounter have developed since the mid-1960s. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 38), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Kroatische katholische Mission, Elisabethkirche, Kassel, 14.04.2017. Luka Ćurić, Gabrijela Juričić, Marin Juričić, Danijel Bralo, and Danijela Juričić are participating in a service at the Church of St. Elizabeth in Kassel. Most of their grandparents arrived in Kassel in the 1970s. Mr. Juričić and his wife, the parents of Gabrijela, Danijela, and Marin, support a bilingual education for their children, both at home and at school. Josip Matuzović who is standing in front of the five altar servers, emigrated to Kassel in 1993 with his whole family to escape the war in the former Yugoslavia. Together with his wife Ana, born in Berlin and a second generation descendant of a guest worker family with roots in Bosnia, Mr. Matuzović is cautious about acquainting their children with Croatian traditions. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 39), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 60 x 40 cm. Türkischer Rentnerverein Emekder, Kassel, 17.03.2017. A visitor to the Emekder meeting room who has not yet retired. The regulars at the retiree association know that he is a second generation guest worker, but are not well acquainted with him. While talking about his father, they discuss that he has been buried in Turkey. The Turkish-Islamic Union for Religious Affairs (DITIB) offers to take the body of a deceased person back to his or her village, against a contribution of €50–60 annually. Even some people who declare Germany to be their new home wish to be buried next to their relatives and ancestors. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 40), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 60 x 40 cm. Türkischer Rentnerverein Emekder, Kassel, 17.03.2017. The photograph on the wall behind the visitor at the meeting room at Emekder depicts Vedat Bilecen, who founded the retiree association in 1993. Mr. Bilecen arrived in Hannover in 1973 as a guest worker and then moved on to Kassel to work at Volkswagen. He retired at the same time as several friends of his at the company. Discussing what to do with their free time they decided to set up an association dealing specifically with the situation of people like themselves. At that time such associations of Turkish people were still rare in Germany. Vahiddin Oğuz, the current president, was asked to draft the statutes, because he was acquainted with the person responsible for a similar association in Hamburg. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 41), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 26,7 cm. Halitplatz, Nordstadt, Kassel, 28.04.2017. On October 1, 2012, Halitplatz was inaugurated in memory of Halit Yozgat, one of the victims murdered by the so-called National Socialist Underground—NSU. The square is located in front of the southeast entrance to Kassel's main cemetery. A street sign and a memorial with a commemorative plaque were erected in the square. The memorial was smeared with black paint in March 2013, and after the event commemorating the eighth anniversary of the victim's death, a black-brown substance was poured over it. The family of the victim wanted Holländische Strasse, where Halit Yozgat was born and murdered, to be renamed Halit-Strasse. "Neo-Nazi criminals murdered ten people in seven German cities between 2000 and 2007: nine fellow citizens, who had found new homes in Germany with their families, and a policewoman. We are shocked and ashamed that these acts of terrorist violence have not been recognized over the years for what they are: murders arising out of contempt for mankind. We say, never again! We mourn for: Enver Şimşek, September 11, 2000, Nuremberg, Abdurrahim Özüdoğru, June 13, 2001, Nuremberg, Süleyman Taşköprü, June 27, 2001, Hamburg, Habil Kılıç, August 29, 2001, Munich, Mehmet Turgut, February 25, 2004, Rostock, Ismail Yaşar, June 5, 2005, Nuremberg, Theodoros Bulgarides, June 15, 2005, Munich, Mehmet Kubaşık, April 4, 2006, Dortmund, Halit Yozgat, April 6, 2006, Kassel, Michèle Kiesewetter, April 25, 2007, Heilbronn. Joint declaration by the cities of Nuremberg, Hamburg, Munich, Rostock, Dortmund, Kassel, and Heilbronn, April 2012." Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 42), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Neriman and Behçet Dinç, Kassel, 09.11.2016. Neriman Dinç came at the age of twenty-four as a guest worker from Istanbul and found work at Kumpe, a brush factory in Mönchehof, near Kassel. Her husband Behçet arrived in December 1973, worked for eleven years at a gardening firm, and then started to work at Volkswagen. Both are now retired. In the picture the couple present their engagement photo from 1967. Their first son was born in 1969 and lived with relatives in Turkey. The child had an accident at the age of five while playing in the water and died. Ms. Dinç's father travelled to Kassel to communicate the bad news in person. He stayed for a few months and left without telling his daughter of the death. One year later she had her second child, who died a month later. In 1975 she had another son, in 1979 a daughter, and in 1986 another son, in Kassel. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 43), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Klinikum Kassel, 20.03.2017. In 1971 Deolinda Lopes Marinho followed her husband, José da Costa, to Germany with three of their sons, Carlo, Paolo, and Toni. Manuel, their second child, remained in Portugal for a further year with his aunt to finish school. Mr. da Costa had arrived in 1966. He moved to Immenhausen near Kassel to work at MEWA, a textile factory. Four Portuguese families who were already living there made the family feel welcome and safe. Ms. Marinho worked various different jobs but never returned to her original profession as a teacher, which makes her sad to this day. During her long stay at Klinikum Kassel hospital, Ms. Marinho has been visited every day by her sons. On her eighty-first birthday, Clara Sakić, a friend, is looking at a drawing by her granddaughter Melina, held by Melina's uncle Manuel. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 44), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Dilber and Can Saltik, Vellmar, 02.03.2017. Dilber and Can Saltik are the wife and grandson of Ibrahim Saltik, who came from Istanbul to Koblenz as a guest worker. From there he went to Rheinland–Pfalz to work for the construction company Hochtief. Because of the 1973 economic crisis he had to find a new job with Ford in Cologne. In 1979 his first two children came to Germany, and because he couldn't find a house in Cologne the family moved to Kassel. His sister was already living there, working at Volkswagen. Mr. Saltik found a job at Mercedes Benz. First they lived in the workers' neighbourhood Nordstadt, then they moved to the neighbourhood Vellmar, where they were the first migrants. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 45), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 26,7 cm. Hortencia María Fragoso Filipe Miguel, Kassel, 21.03.2017. Being deeply religious and praying several times a day, Hortencia María Fragoso Filipe Miguel received most of the figures on the altar in her room as presents from her children and grandchildren. She lives in Kassel with the family of her daughter, María Alzira Filipe de Jesus. Ms. Miguel came to Germany at the age of thirty-seven in 1971 to join her husband, who had arrived one year earlier. Her daughter explained that, for her mother and herself, home is the place where her family is. She added, however, that her husband, Juan Lozano Marchena, considers Kassel his home, but that his heart belongs in Algodonales in Andalusia, the place where he was born and his family still lives. Mr. Marchena came to Germany with his parents when he was six months old and grew up in the Bettenhausen neighbourhood. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 46), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Feria de Abril, Club Juvenil, Kulturzentrum Schlachthof, Kassel, 23.04.2017. Stella Felicitas Levien is being prepared by her mother, Marija Levien, to participate in a flamenco performance, together with other children and her teacher, Maria Lopez. Ms. Lopez runs the dance school La Marivi, where flamenco classes are mostly taken by the children of third generation Spanish guest workers, but also by local children. The joint performance is part of the Feria de Abril (April Celebration), organized every year at the Schlachthof cultural centre by the Spanish youth club, Club Juvenil. Besides dance and music, visitors are treated to paella, tapas, and wine. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 47), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. FC Bosporus Kassel, 09.03.2017. The Turkish Folk Song Choir rehearses once a week under choirmaster Haki Ayalp at the clubhouse of FC Bosporus, but it is independent of the soccer club. The choir is a social project, initiated by the people involved; singing is for them a way to preserve relations with the culture of their origin and to transmit it to the next generation. Everyone feels differently about their home. Aynur Gökdere doesn't feel at home in Germany; home for her is Turkey. Aysun Şen arrived at the age of eighteen, has two children, and considers Germany her home. She loves to go to Turkey on holiday, but every time she is there she misses Germany. Even though Senem Duman was born in Germany, her home is in Turkey. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 48), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Gemeindesaal Markuskirche, Kassel, 06.03.2017. In the church hall of the Church of St. Marcus, the Association of Transylvanian Saxons organizes an afternoon coffee reunion for elderly people of German descent, who emigrated from Transylvania. They sing folk songs, exchange memories, and consider such meetings very important for preserving their native culture. The chairman of the association, Michael Theuerkauf (second from left) escaped from Stolzenburg to Kassel in 1981, when the German minority in Romania was suffereing increasing oppression. Mr. Theuerkauf now has his family, his children, and his grandchildren in Germany, but the culture that is important to him is rooted in Transylvania. After the fall of Nicolae Ceaușescu he returned again to his parents' farm. The family who lived there hadn't maintained it, because they had been afraid the Germans might return. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 49), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Islamisches Gräberfeld, Westfriedhof, Kassel, 26.03.2017. Since 2014 it has been possible to bury a Muslim's body without a coffin at the Kassel Westfriedhof (Western Cemetery) in Süsterfeld-Helleböhn. In order to facilitate what is considered in Germany to be an unusual manner of burial, the Hessian Cemetery and Burial Act had to be changed. The picture shows fresh graves in the Islamic section of the cemetery. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 50), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Nordstadt, Kassel, 23.03.2017. The development of Kassel Nordstadt along Holländische Strasse is closely linked to the city's industrialization in the nineteenth century. Connection to the railway system facilitated the establishment of important companies such as Henschel & Sohn (which made locomotives, and during the Second World War, tanks, airplanes, etc.), Gottschalk (which made textiles)—both of which have been replaced by the university—and the slaughterhouse, which today is the site of the Schlachthof Cultural Center. The industrial units were interspersed with workers' neighborhoods. With the decline of industry in the 1970s, the previously working class population was replaced by a population of immigrants. The presence of students and immigrants in turn changed Nordstadt's infrastructure. Today it is dominated by immigrants' shops, bars, and venues for alternative cultures. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 51), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. FC Bosporus Kassel, 23.03.2017. Initially, FC Bosporus had rooms at the Schlachthof cultural center and was called Genclerbirligi (The Youth Union). However, the leftist inclinations of the board meant that it became notorious for its alleged communism, and increasing numbers of parents prevented their children from joining the club. As a consequence, it was decided to leave the Schlachthof premises. After moving a number of times, always around the Nordstadt district, approximately ten years ago eight players guaranteed the payment of a loan and the club was able to buy the pavilion next to the Nordstadt Stadium. The new premises have offices and rooms for social activities, in addition to spaces for sport. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 52), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 40 × 60 cm. Mattenberg, Kassel, 21.03.2017. In the Nazi period a model housing project had been planned to extend across the areas of Oberzwehren, Mattenberg, and Nordshausen. Until the beginning of the war, however, only parts of the project could be implemented, and were inhabited by skilled workers predominantly from the west of Germany. Starting in 1940, the outskirts of Mattenberg were covered with barracks to house forced labourers from all over Europe. In 1945 the US military administration confiscated the complete housing estate to make it available for displaced persons. The German inhabitants had to leave within one hour. In 1949 the estate was returned, but many flats remained unoccupied, and deteriorated. In the 1960s guest workers, mostly from Turkey, started to settle in Mattenberg. In 2014 a mosque was inaugurated here after a lengthy construction period of six years. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |

|

Ahlam Shibli, untitled (Heimat no. 53), Nordhessen, Germany, 2016–17, chromogenic print, 60 × 40 cm. Kassel Merkez Camii, 24.02.2017. The Kassel City Mosque located in Nordstadt is run by an association of more than 200 members, each of whom contributes 10 to 20 euro per month. Additional funds are collected on festive occasions such as Ramadan and Eid al-Adha. The mosque is affiliated to the Turkish-Islamic Union for Religious Affairs (DITIB), which in turn is controlled by the Presidency of Religious Affairs, an Ankara-based state organization. DITIB allocates Imams to mosques and pays their salaries. Apart from prayers, the association offers cultural programs such as trips for senior citizens to Wartburg Castle, Quran lessons in Arabic, or classes on Ethics. A former member of the board of the mosque association emphasizes good relations with the municipality ("They don't keep us out"), the representation of other faiths, and schools. Courtesy of the artist, © Ahlam Shibli |